Preserving Seasons #1: Rhubarb-Ramp Kimchi

Adaptable, so versatile and packed with tons of flavor and umami.

A delicious way to use up Rhubarb beyond sweet delicacies.

When making Rhubarb Kimchi, using greens is a personal choice but if you aren’t a big fan of the sour/ tart flavour profiles, the addition of greens does wonders. And Ramps take the flavour profile of this Kimchi to another level really. Its pungency complements and balances both Rhubarb’s tartness and Kimchi’s natural sourness.

However, with ramp season is now over, you can substitute it with Beetroot greens. While it doesn't lend a similar pungency as Ramps, it is equally delicious. I’ve made multiple batches of it last year. Toasted & lightly buttered challah paired with this kimchi was such a pleasant revelation and a big hit during get-togethers.

Fresh Beet-greens have already started making an appearance at the farmers’ markets so now is a good time to preserve this season’s goodness at its best. I’m myself making another batch with them very soon as my jar of Rhubarb-Ramp Kimchi would only last another week.

For all those who are new to Ramps, what makes them so special?

Ramps, are spring’s special goodness that are from the allium family. Also called as wild leeks (confusingly so because they are not leeks) are native to the woodlands of North America. They grow in Eastern Canada and in the U.S and are super seasonal. Their flavour is uniquely pungent and is described as a combination of both garlic and onions.

Ramps have to be responsibly foraged as they grow very slowly and take up to 4 or more years to flower and reproduce.

Sharing some interesting tidbits I learned about Rhubarb from the Delicious Bits Newsletter by Elizabeth Pizzinato.

Rhubarb fans are legion, nowhere more so than in Britain and North America, where this humble plant has found its way onto the dessert course for hundreds of years. But rhubarb didn’t start its journey as a compote, cake, cordial or jam.

The Chinese first discovered rhubarb’s astringency to be effective as a laxative. Ancient Greeks and Romans carried on rhubarb’s medicinal tradition, and gave rhubarb its modern name. Rhubarb derives from the Latin rhabarbarum – rheum, the plant genus of which rhubarb is a cultivar, and barbarum, the Latin for barbarian.

It wasn’t until the 1800s that rhubarb’s culinary prowess came to the fore. According to Dennis Duncan of High Altitude Rhubarb, widespread consumption of rhubarb began in Britain in the early 19th century, growing in popularity as an ingredient in desserts and wine making. With a short growing season, the discovery that rhubarb could be “forced” (grown out of season in the winter), caused its popularity to reach fever pitch, peaking just before World War II.

And this is where the most romantic part of rhubarb’s history comes into play.

This recipe is adapted from Kristen Shockey’s Rhubarb Kimchi recipe. This version is a simpler one with ingredients I already had in my pantry.

Recipe notes

Any fermentation experiment is more about the process than the recipe itself. This process can easily be tweaked based on the quantity of ingredients you have in hand. All you’ll have to adjust is the salt proportions.

Salt for this recipe is at 3%. It is calculated as 3% of the total weight of all the ingredients.

If you prefer more heat in your Kimchi, you can increase the quantity of Gochugaru. Do not hesitate to substitute Gochugaru with any other chili flakes available locally to you.

In this recipe, I have used both the milder green tops and the stronger-tasting bulbs of Ramps.

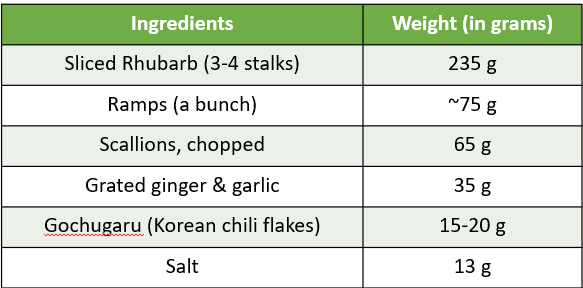

Ingredient Card

Process

Thoroughly wash both Rhubarb & Ramps before your mise en place.

Thinly slice the Rhubarbs.

Finely chop up the ramps & scallions.

Grate ginger & garlic.

Now add all the ingredients together in a bowl & get ready for the fun part of this recipe. You might want to wear a glove for this next step.

Massage everything together to allow Rhubarb to release some of its juices. You’ll end up with a chunky yet juicy mixture.

Transfer the mixture to a jar pressing down the contents as you go to remove any air pockets and keeping the kimchi submerged in its own liquid.

You can either top the kimchi with a zip lock bag filled with water or cut a circular piece of parchment paper. This will allow the ferment to do its own thing without any interference from unwanted microbes in the external environment.

Let the kimchi to ferment at room temperature for 4-5 days until both, the colours and flavours have mellowed down a bit and the ferment has developed enough acidity lending a tanginess. If you prefer more sourness, let it ferment for a couple more days.

Remove the parchment and transfer to fridge where the kimchi can be stored for upto 6 months. Highly doubt it’ll last that long unless you make a bigger batch which I’d highly recommend - that too before the Rhubarb season gets over.

Happy Fermenting!